Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter has motivated me to stop using the platform and start thinking about other, older ways of thinking in public again. Prior to Musk taking the company private again, I had largely stopped using the platform to communicate with others in any meaningful way. It became a site to get news and hear the inner monologues of a few interesting people, but those accounts had grown few and far between. Mostly I seemed to be reading about narrow bands of interest from interesting people or watching journalists practice an extension of their (paid) work as writers. All of this has been accompanied by a shift towards live-performance on Instagram and TikTok, which I have little interest engaging with. As a ‘word person’, I had also stopped writing and thinking in forms longer than a caption outside of my art or the occasional writing project. I don’t think I’m going to return to regular blogging, but I do think there is something to returning to a space where I can think out loud when no one is looking. I imagine anyone reading this has decided to visit this site looking for a particular art work or some piece of information. It is an island in a sea of information and does not have to perform in an attention economy. Anyway, it’s ironic that the democratizing platform of Twitter has ended up in the hands of a billionaire who is looking to turn Twitter into a profit-engine. It’s something that would fit neatly into one of my more dystopian timelines about the contemporary era which has seen some of the worst effects of wealth and income inequality come to pass, including the erosion of democratic institutions that Thomas Piketty warned about in Capital in the 21st Century. So, you won’t find me active on Twitter anymore @powhida, but I’m leaving the account there as a digital headstone for over a decade of sometimes interesting and often embarrassing public engagement about being an artist in New York. #RIPDrunkartist

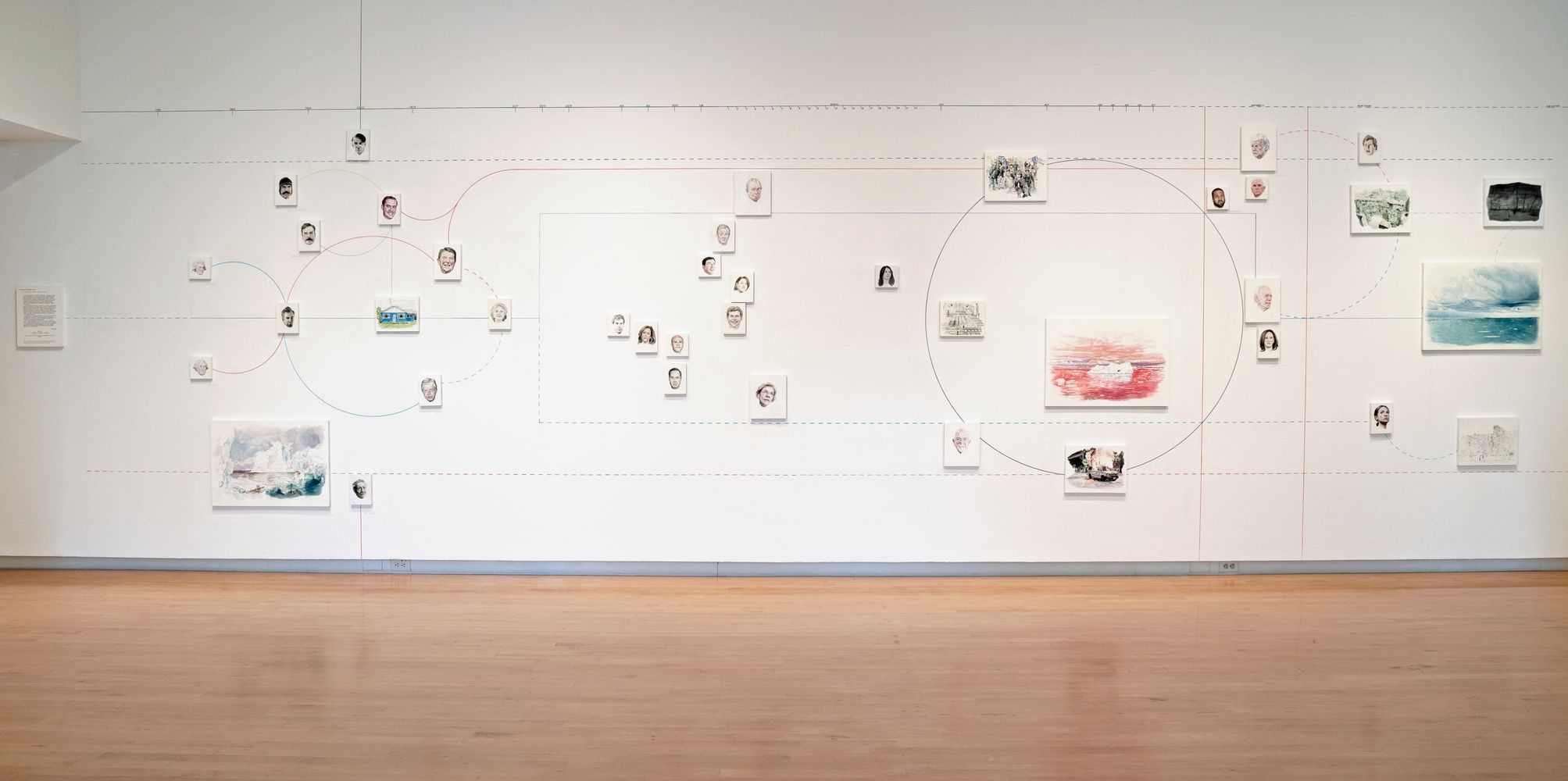

I’m nervous to present documentation from my installation, Possibilities for Representation, at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art included in Twenty Twenty. I’m nervous and filled with anxiety about the outcome of the coming election and what it will mean for the subsequent iterations of the installation. The exhibition, organized by Exhibitions Director Richard Klein, features several artists whose work addresses the politically-charged moment with works on paper drawn from photographic sources. All of the artists have been invited to add, subtract, or modify their contributions to the show. I started work on the paintings for the show back in January to prepare for a June opening that was interrupted along with the rest of the world until October of this year. The individual works are currently for sale, much like the politicians depicted in the works who depend on private money to fund their campaigns. This decision is explained in a little more detail in the note included in the installation, but is not entirely commentary on campaign finance. It is also commentary on the economic impact of COVID on artists and galleries. The Aldrich is not a collecting museum, so selling the work out of the exhibition is less fraught than the current austerity-driven deaccessioning happening across the country as museums struggle to deal with lost revenue and the important work of expanding the representation of their current collections. While there are important reasons for museums to sell works held in the public trust, it is still no less painful to see how museums are putting works back into speculative markets. I think it would feel similar to seeing a property held in a public land trust be dismantled and sold to private developers. In a less fucked up world donors, patrons, and the government would provide the funds necessary to support museum workers and begin new acquisitions campaigns to add under-represented artists (rather than engaging in expensive capital campaigns to expand their physical footprints). Right now, that isn’t a cultural or political reality, so it’s with some ambivalence that I accept there are urgent needs met by what might be described as “recapitalization” - returning work held in the public trust back into private hands due to a lack of public funding. It is difficult to put art, often held in storage and out of sight, before the needs of people. It just seems too much like an austerity measure and indictment of the lack of progress by museums to expand their holdings of art instead of expanding their spaces.

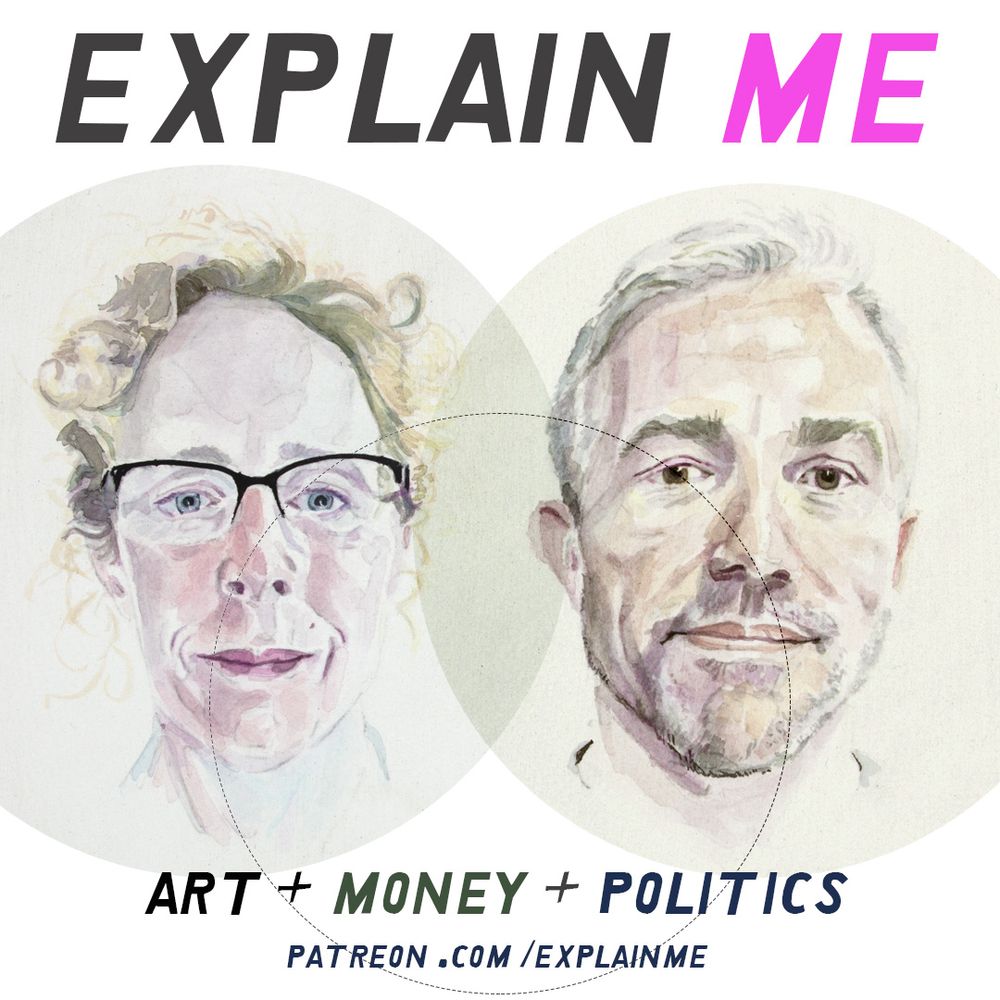

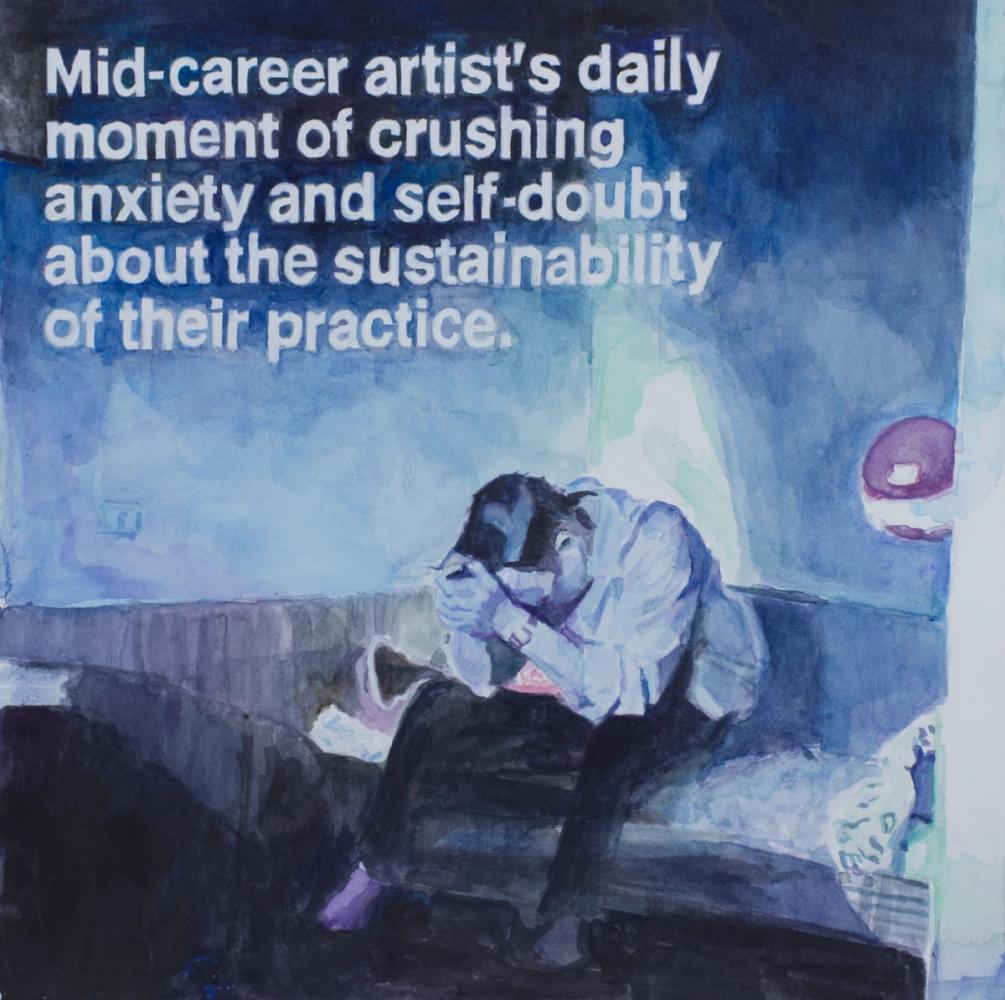

Paddy Johnson and I have decided to launch a Patreon campaign to help fund our podcast Explain Me. After a year-long hiatus, we returned with two episodes this year, which found us discussing the spring art fairs as the Corona virus pandemic unfolded around us, and a recent conversation about the impact of the “pause” on the art industry with Ateiler 4’s Jonathan Schwartz and my art dealer, Magda Sawon of Postmasters Gallery. Part of the reason we took a year off is due to the amount of work planning, recording, and editing a podcast takes while we have both been pursuing more freelance and adjunct teaching work to support our critical and artistic practices. It made the time commitment necessary to record and publish_ Explain Me_ on a monthly basis difficult for us, but we both really enjoy the work. To that end, we have launched the Patreon campaign to raise enough money to produce at least 3 - 4 episodes of _Explain Me_ each year with a goal of raising enough money from our listeners to record a new episode every two weeks. We understand that might challenging, particularly at this difficult moment, but we have to start somewhere. If you enjoy listening to _Explain Me_, please consider supporting our discussions of the way art, money, and politics intersect in the art-industrial complex. All of our previous and future episodes will remain available for free, but we can’t do it without the support of our core listeners. If you’re new to _Explain Me_, all of the episodes are available through Apple Podcasts, and I hope that you’ll give it a listen as we continue to record new episodes this spring and summer. If you find the episodes of interest, we welcome your financial support. https://www.patreon.com/explainme

I’ve launched a new project called Store-to-Own that invites the public to store available works from my personal inventory in their homes, offices, businesses, or institutions. After a period of five years, title of the works transfers to the borrower, while I retain a 50% stake in any future sale of the work based on a simple contract Amy Whitaker and Alfred Steiner wrote for me. The project is hosted on a Google Site that you can access here. I will update the site with inventory that returns to me from the last 16 years of exhibitions. The contract is also freely available for modification and use by anyone who has art in storage they would prefer to have out in the world. Embedded in the contract is also a re-sale rider that introduces a resale royalty currently unavailable to artists in the U.S., unless of course, we make that part of all of our contracts.

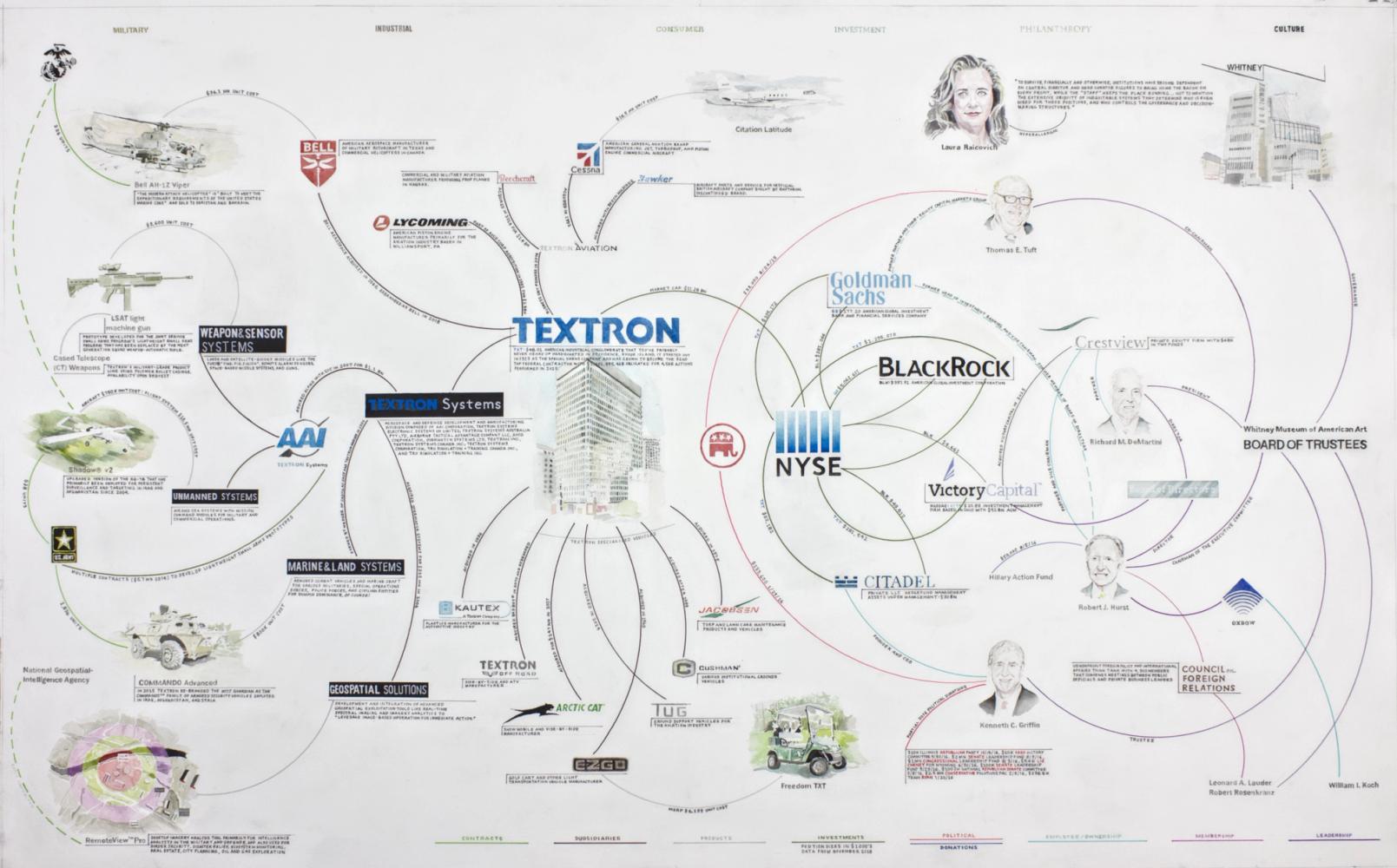

High-resolution images from the exhibition are now published here. September 7 - October 12, 2019 _opening reception, Saturday 6-8pm_Postmasters Gallery is pleased to announce Complicities, William Powhida’s first solo exhibition with the gallery in nearly five years (and almost a decade since the Brooklyn Rail published “How the New Museum Committed Suicide with Banality”). Complicities is a show of painfully obvious, politically didactic, research-based, and precisely rendered works on paper. Produced over the last ten months in the wake of the crisis at the Whitney Museum, the work makes visible generalized and abstract systems —investment, real estate, museum boards, private family-owned companies, curation, public policy —illuminating the connections between art and the ruling class. Through specific subjects and case studies, Powhida uses an aesthetic of what might be best described as ‘capitalist realism’ to render an image of neoliberal governance and art’s instrumentalization in perpetuating a system of private-public partnerships. Punctuating these slow takes are a series of paintings based on the artist’s Instagram memes drawn from films and series including Halloween, Don’t Look Now, The Terminator, Robocop, Chernobyl, and Billions, which offer a different kind and degree of reflections on art’s role in society. Over the last decade the need for critical re-evaluations of American social and cultural governance continue to intensify as the degrees and layers of structural, systemic, pragmatic, and opportunistic ‘complicities’ are laid bare. The private and public systems that William Powhida maps out involve a lot of powerful white people. The artist visualizes financial investments in a military and defense conglomerate by four Whitney board members; the corporate web of profit, violations, lobbying, and philanthropy of the Koch Brothers’ sprawling empire; the policies and investments behind developer Stephen A. Ross’s Hudson Yard’s project initiated by former major Michael Bloomberg; laws and executive orders behind privatization since President Reagan; the direct flow of businessman Warren B. Kanders’tear gas to his previous role as a trustee at the Whitney Museum; and the curatorial structure of the Venice Biennale. The artist has described the resulting works as a form of ‘capitalist realism’ –a data visualization made of charts, diagrams and annotations filled with his exquisite watercolor drawings. He is attempting to put information back into circulation as art– the thing that links all of his subjects together. Through a companion series of Instagram memes largely drawn from science fiction and horror, the artist comments on the institution of critique – “political art is a joke” – but as Kanders’ resignation from the Whitney Board shows, there are, in fact, ways to engage institutional critique outside of the studio. As the _Teargas Biennial _essay, the _Decolonize this Place _protests, and the withdrawal of 9 artists from the Whitney Biennial demonstrate, internal and external pressure can compel institutions to change. Nan Goldin’s efforts and lawsuits, brought by five states, representing thousands of victims, have caused museums to sever ties with the Sacklers and ask existential questions about their relationship with structural inequality. Artsy’s Nate Freeman recently reminded us that it’s been nearly 10 years since Greek mega-collector Dakis Joannou purchased a $1,000 William Powhida print How the New Museum Committed Suicide with Banality. It is a drawing “that satirizes the various players in the scandal and maps out all their connections, brutally criticizing the institution and its benefactor. ”Freeman’s observation, beyond suggesting Mr. Joannou has a sense of humor, implies that Powhida’s own complicity in the systems — museums, the art market, social media, white male privilege —undercuts or negates the function of critique. Powhida it would seem, is already bought and compromised. At the risk of centering structural problems on himself the artist has long been engaged through satire, parody, and self-critique of the problem of his identity as an artist. A crucial aspect of this problem is best articulated by artist Xaviera Simmons, “Understand the historical American narrative and see yourselves within that framework; do the cultural autopsy, name what whiteness is and the centuries of harm it has done; show yourselves to each other and wrestle with the implications of whiteness on canvas, in performance, in front of the camera and definitely in writing; and, most importantly, stop oppressing us through dismissive and condescending words and deeds.” William Powhida has no illusions that this work will change the systems he inhabits, or save anyone, but he will not be selling any of this work to any of the subjects depicted (sorry, Glenn Furhman!). The artist will make any information about sales that transform art into commodity public upon request and tell you some other things about unpaid labor.