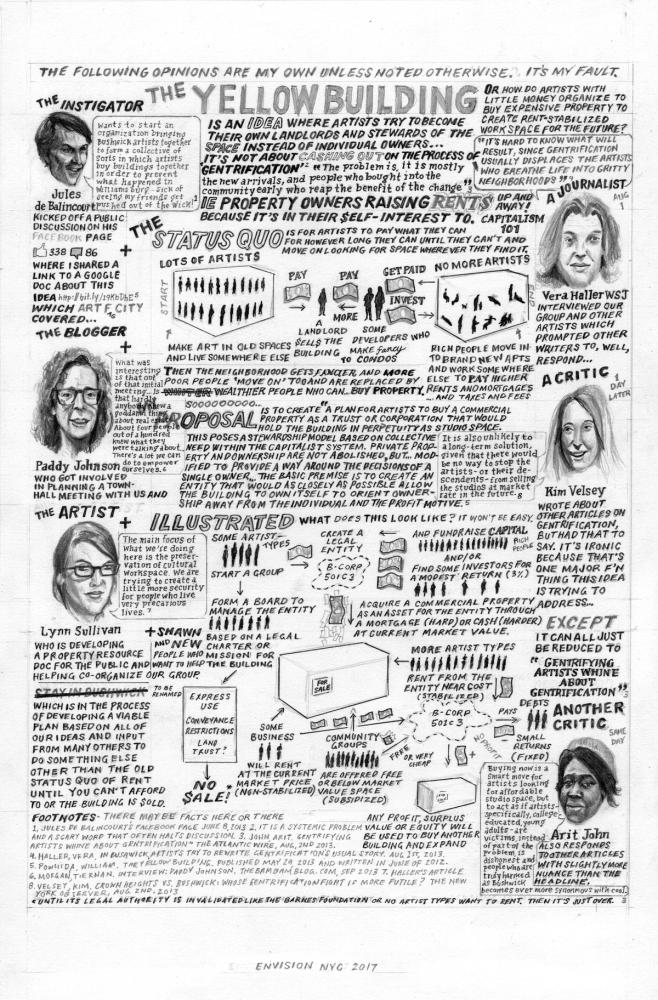

Jennifer McCoy joined me in hosting a discussion around higher education in the arts at Joe Riley, Casey Golan, and Victoria Sobel’s class They Can’t Kill Us All at Bruce High Quality Foundation. Here’s the introductory text. I also recently published a rather long-read on individual and collective property ownership on Big, Red, and Shiny. I have to thank editor John Pyper for prodding me to contribute to the journal. The piece was inspired by the work I’ve been doing with Jules deBalincourt, Paddy Johnson, and Lynn Sullivan to create stable studio space in New York. I also contributed a drawing proposal “The Yellow Building” to MoreArt.org’s project_ Envision NY 2017_. Artist Caroline Woolard also recently shared a link to her project bfamfaphd about organizing artists to make alternative investments in their own education and working conditions. Woolard’s project brings together these two incredibly important issues for artists and non-artists; property and education.

Kim Stanley Robinson spoke yesterday at PS1 as part of Triple Canopy’s series “The Future is _______”. Robinson’s clear-eyed and sensible speculation about the future was the sort of reasoning one might wish to hear coming from the president and Congress. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely we will see our state begin the kind of Utopian planning Robinson calls for before we “cook ourselves” burning 2,000 gigatons of available carbon over the next thirty to fifty years. Robinson’s description of “the long emergency” is part of the catastrophe narrative of climate change, population growth, and predatory dumping by capitalist markets. In a moment of bleak humor, Robinson said the reality of the catastrophe narrative “won’t even be as fun as The Road.” The conditions of a catastrophic rise in water levels for example would be like a thousand Katrinas and that he wouldn’t be worried about the survival of democratic government, he’s more worried about the survival of the species. In short, the long emergency isn’t about changing quality of life, but a possible extinction event. In the face of the gloom and doom, Robinson’s ideas about Utopia are based in reasonable consumption of resources and a notion of adequacy. This is the “how much is enough?” question, or a matter of degree. Robinson highlighted the efforts of the 2,000 watt society in Switzerland as an example of a model of adequacy in modern life. The city of Zurich has voted to adopt the policies of the 2,000 watt society by 2030 countrywide. It’s a compelling counter-narrative to the ‘grey jumpsuit’ fear mongering about equitable distribution of energy. So, when Robinson talks about Utopia, he’s not talking about a place of our dreams, but a world the provides food, housing, healthcare, education; the foundations of happiness.

To this end, the root of the long emergency lies in the “bad economics we live in and the market.” Robinson describes the fallacy of ‘free-markets’ talking specifically about predatory dumping, the practice of pumping products into the market at artificially low-rates. He expanded on the economic definition to suggest that our economy systematically under-prices commodities by shifting things like environmental costs to the future. This creates what Robinson calls an inter-generational ponzi scheme, which requires in response multi-generational Utopian projects to plan for the necessary correction when the ponzi scheme goes bust. To do this, Robinson believes we need to use science against Capitalism, just as science brought about the Enlightenment, it can be used to lift us out of the residual feudalism of Capitalism and our new aristocracy of inequality. Robinson reasons that capitalism is a bad social technology or economic technology making it a bad model for dealing with the long emergency. He specifically talked about the financial cost of not burning that 2,000 gigatons of carbon in the earth, it’s worth $1,600 trillion. What capitalist is going to leave that much money in the earth? This is why, Robinson argues, that we need new economic models other than capitalism to contend with the consequences of our consumer lifestyles. In a light moment, Robinson says it’s a matter of style. “Do you want good style or bad style? Do you want to be a fat rich person in a gated community?” The alternative being a fuller, richer social life in the company of friends and family with less material luxury. This requires us to consider what are necessities, and what we can live adequately without. Ultimately, someone in the audience asked “why are you drinking out of a plastic water bottle?” Robinson, a little chagrined, describe his low-carbon footprint lifestyle back in Davis, California, a very bike-friendly community, but the moment captured Robinson’s closing remarks that the way forward is messy, and there is no single solution. He referenced philosopher Karl Popper’s term monocausotaxophilia, wherein people believe in a single solution like God or Freedom to all of the manifold, interrelated problems of our increasingly complex society. But, Robinson warns, there is no magic bullet and maintaining the status quo is now part of the catastrophe narrative. Robinson’s keynote lecture was an excellent rejoinder to Slavo Zizek’s assertion that the looming threat of ecological is one the major social antagonisms that require us to imagine society after capitalism.

Dismissed Acclaimed provincial New York-based artist William Powhida is pleased to announce Bill by Bill, a new collection of art works fabricated exclusively for Charlie James Gallery and the fast-growing Los Angeles art market. Conceptualized and designed by William each work of art has been crafted by better highly skilled artists, designers, friends, family and fabricators under the artist’s supervision in a studio he visited at least once. After years of going to art fairs intensive market research _Bill by Bill represents a decisive breakthrough for the artist into the fields of sculpture and painting by creating unique variations on some of the dominant formulas trends in contemporary art. Bill by Bill brings together classic Modernist forms with bleeding edge post-studio, conceptually based[1] practices to create a mercenary_stunning vision of contemporary art. Begun over a year ago while on residency at the Headlands in beautiful Marin County, William has designed a line of auction-ready commodities objects across stylistic boundaries for market-savvy executive producers collectors. These objects are primed and ready for purchase to move quickly at Phillips de Pury. With a focus on painting and sculpture Bill by Bill avoids problems of reproducibility inherent with photography, new media, multiples, and editions which have diminished the deep satisfaction of buying art. These one-of-kind objects are able to offer the ‘experience of art’ at a price that isn’t quite for everyone, which affirms William’s belief that art holds an elitist special place in culture. A unique, signed certificate of authenticity in the artist’s signature style accompanies[2] each hand-touched[3] object. The certificate provides the artist’s critical insight into the fascinating design and fabrication process behind each work. These intimate, text-based certificates contextualize each object in a theoretical and aesthetic discourse while situating them in the broader social and political space of neo-liberal capitalism late modernity. Charlie James Gallery is relieved pleased to finally bring this moyen-garde model of art production and distribution to Los Angeles, which we believe is the only city capable of buying this. William Powhida was born in 1976 in Ballston Spa, New York. Powhida has no upcoming exhibitions at any major art institutions. Recent exhibitions include “Market Value: Examining Wealth and Worth” at Columbia College in Chicago, IL; “On Sincerity” at Boston Collegein Boston, MA; (2012), “Seditions” at McKinney Avenue Contemporary in Dallas, TX (2012), “Derivatives” at Postmasters Gallery, NY (2011) and Dublin Contemporary in Dublin, Ireland (2011). His work has been discussed in October, Art in America, Art Forum, The Brooklyn Rail, Frieze, New York Magazine, and the New York Times. His art was recently featured in the Village Voice, America’s oldest corporate-owned alternative weekly. Image: Installation shot: _Bill by Bill _courtesy of Charlie James Gallery [1] This does not mean conceptual. [2] The collector agrees to purchase the certificate of authenticity to receive the object. [3] The artist may have only touched to the work indirectly receiving the work or crating it.

[caption id=“attachment_2085” align=“aligncenter” width=“1102”]

Relational Wall, Watercolor, colored pencil, and graphite on panel, 2009[/caption] This isn’t a formal essay, but the thoughts might be worth sharing. Today, I think the art world, all of them, feels a little bit like MoCA. The situation there is an interesting intersection of everything that is going on in both the market and the museum world in relation to broader economic trends, which I hope most of us are aware of. MoCA is struggling to maintain their independence as an institution, but is desperately beholden to its board members and trustees for money, and sort of got into this mess when it leaned too heavily on one oligarch in particular, Eli Broad. Mr. Broad bailed out the museum a couple of years ago with $30 million in exhibition funding, which had some explicit and implicit strings attached to it. The donation included explicit conditions such as the ‘No merger with any institutions within a 100 mile’ clause, and less explicit ones like the addition of New York art dealer Jeffrey Deitch as the new Director of the museum. That decision hasn’t exactly worked out since Deitch’s main task was to raise money for the museum, and not to curate the shows, which was Paul Schimmel’s job. While popular shows and attendance figures look good, museums typically only generate anywhere from 3-11% of their operating revenue at the gate. I believe all museums should be free to the public, and free to curate whatever shows they want, not ones that are engineered primarily to attract crowds. Still, any loss of revenue is important to a museum, and that money could translate directly into staff positions. Unfortunately, Deitch’s gambit to make the museum relevant to the public with shows like ‘Art in the Streets’ didn’t make museum-rescuing money or lead to big time donations. Pretty much all the artists, minus four, quit the board when Deitch allowed the dismissal of Schimmel. So the museum finds itself caught in a power struggle between Michael Govan and his allies at LaCMA and Mr. Broad. Probably just Mr. Broad, alone with his money, foundation, and own museum being built near MoCA. Even Roberta Smith, whose consistency of judgment I often question, called for MoCA to distance itself Mr. Broad to strengthen the institution. Apparently, a healthy board requires more than just one rich person’s vision, which included fucking over LaCMA by not donating works to their permanent collection and allowing his foundation to retain ownership of the works loaned to BCAM. That wing of LaCMA is like a Russian nesting doll, a privately funded museum within LaCMA, but not exactly of LaCMA. BCAM has it’s own funding and staff paid for by Mr. Broad, and shows work from his foundation, which is held in public trust, but privately administered according to Mr. Broad’s wishes. The Rubell Family Collection does a fair job of describing this model of public-private and private-private model of foundation/museum collaborations. Also of note is Rob Reich’s recent piece on the role of private foundations in our questionably democratic society, which reads something like “the wisdom of plutocracy”. MoCA is currently trying to raise a $100 million endowment, which if fully-funded, would generate enough interest to pay about 30% of the museum’s annual operating budget. While that would be a solid base compared the current reliance on Mr. Broad’s conditional and soon-to-expire funding, this all a lot of talk to say that they are still fucked financially. To continue operating, they will still have to raise a great deal of money through fundraising, which puts them in the same position as the rest of the art world, reliance on the beneficence of the 1% or the .01% to be more precise. This is the condition that society finds itself after decades of neoliberal policies that have promoted privatization of pretty much everything in society from education to prisons to museums. The dictum is basically, “make everything more efficient with Capitalism!” How well these policies work is entirely dependent on how you think the world is doing, and not just our society. Obviously things continue to churn along and work to the degree that you are satisfied or dissatisfied with your quality of life. I am not convinced that neoliberal capitalism is the end of history, and the system we have all been waiting for or that it serves the public interest and promotes the general welfare of the citizenry (which we are obliged to do). The main evidence of the failure lies in the concentration of wealth in the hands people like Mr. Broad and other oligarchs like Bill Gates, who find themselves in positions of shaping not only culture, but public policy. Mr. Gates' foundation funded the small schools movement here in New York City, and I wonder about his qualifications as an educator. His views on education are backed by an enormous amount of money and what he says will continue to shape the reform movement in American education. I’d rather see local communities or at least educators and academics working with the government to shape sane policy. Regardless, the continued concentration of wealth at the very top of society is having outcomes in the art world that are not very encouraging. Nicole Klagsburn announced today that she’s closing her gallery after 30 years in business, because she doesn’t like the direction the market has oriented art towards; fairs, fairs, biennials, events, fairs, and more fairs. It’s a shame to hear about someone well-respected in the art community calling it a day. Chris D’Amelio was a little more mercenary in his reasoning when he cited the constant economic pressure facing even upper-tier galleries in his decision to ' spread his wings and fly over the chasm' that now divides the top of the art world from everything else. My own gallery is moving to the Lower East Side after their rent was increased to $30k a month. That would mean Magda and Tamas would have to sell $720k in contemporary art in the primary market a year just to pay the rent and the artists, and likely a million just to break even. What they would have to sell to live on? I don’t know, but that is a difficult proposition in an art market where prices are increasing at the top for a few galleries and artists. Leo Keonig is set to take over Postmaster’s old space, and he owns a gallery that has basically had a 100% turnover in artists since the infamous article, “The Businessman” was written about him in 2005. Indeed, he runs his gallery like a business, but that’s not the model I imagine Nicole Klagsburn or Magda and Tamas are interested in. Klagsburn cited the lack of time she had to develop relationships with her artists as one of the reasons she is moving on to a different model. What you and I lose is another opportunity to see art for free on a regular basis. Ed Winkleman, who I’ve known since he ran Plus Ultra in a shoebox in Williamsburg in 2003, recently posted excerpts from an excellent diagnostic essay by Alain Servais on the ‘grow or go’ model facing the commercial art world, which is at the heart of the big-boxification of Chelsea; quite literally expand or leave. Servais gets at a trend he describes as the consolidation of VBA’s (very bankable artists) in the hands of a few mega galleries like Gagosian or Hauser & Wirth. This destroys what Robert Storr describes as the ‘record store’ gallery model, where there are a couple of bankable artists who sell alot, which supports a more diverse program that might not sell very well. In the big box model, every show has to sell well to cover the staggering operating costs of these museum-like operations from staffing to producing publications that confirm the value of the artists' work. In this model we face a kind of homogenization of taste oriented towards the 1% who can afford the attendant high prices like a $100k Dan Colen gum painting. Whether or not you like what Gagosian or Zwirner show is almost irrelevant to the situation, which is our participation in a highly-stratified economy where very few people have most of the wealth, which we must increasingly orient ourselves towards like a plant growing towards the light. I don’t know if any of you [students] plan on opening a gallery, I would be skeptical of only looking at successful dealers. You have no idea how they actually succeeded and what role personal connections, independent wealth, or luck played in that success. There are always a few winners in our Capitalist model and then there is what Zizek describes in his essay “It’s the Political Economy, Stupid”

“I know very well the risks I am courting, even the inevitability of the final collapse, but nonetheless…I can protract the collapse a little bit more, take a little bit greater risk, and so on indefinitely”

I’d encourage you to talk to a lot of dealers and get as much of a sense of the reality of the business as you can, since the gallery model relies all-too heavily on the perception of success, requiring them to appear to be operating out of a condition of excellence versus a condition of need (or likely desperation). The opacity of the private gallery model will prevent you from getting accurate information, which ironically, Capitalism works worse without. It’s a general rule in the art world that we don’t talk about money, primarily because it’s not just about one individual, but a series of interconnected interests, which makes it bad for everybody when we go into detail. “Don’t ask me”. These are just some of the reasons why the art world feels a little bit like the situation MoCA faces, as if we are all MoCA; cash strapped, beholden to rich people, and in bed with the market (in the broadest sense of Capitalism). At this point, it is time to seriously consider alternative economies, new models, and different approaches to the production and distribution of art. This isn’t easy for many of us who have been trained to be studio artists or have run galleries for decades, and I hope we begin this work in spite of income inequality, not because it is the only option left to us by the oligarchs and the tyranny of taste backed by concentrated wealth.

Supreme Digital and Arts in Bushwick have partnered to release a benefit print edition of “Things I Think About When I Think About Bushwick” to support BOS 2012. While I love to hate Bushwick, it has been my home for almost four years now and I’m happy to support the efforts of BOS to pry open artists studios and force them to admit the public. The print is an edition of 40 with 85% of the proceeds going to BOS. My only request was that BOS and Supreme Digital offer an artists honorarium in hopes that small fees might become part of the landscape of benefit requests. More broadly, I hope it becomes part of the discussion for all arts organizations who want to support artists.

To that end, I’m buying one of the prints with my honorarium and will spend the remaining $37 bucks ($150 + tax!) on some beers at Bodega or Ghia or maybe the Narrows. I can never decide. So I hope you’ll support BOS and buy a print that is a little bit of my own Bushwick ambivalence for wherever you art. Image: 16" x 20", Pigmented Print on Hot Press 330 gsm paper by Supreme Digital